This lovely specimen accompanied a new puppy that was in to see us last week. It measures 21.6″ long! A species of Tapeworm, these long, flatworms live in your pet’s intestinal tract and take valuable nutrients from the food your pet eats. The tapeworm most people are familiar with is Dipylidium caninum, a species transmitted by the ingestion of fleas by your pet. But there are several other species that can infect your pet out there.

Tapeworm eggs are heavy by comparison, and not often found with the usual fecal flotation testing (Stool material is mixed with a special liquid that causes the parasite eggs to float to the surface). Segments can sometimes be seen as they exit the infected hosts’ rectum, but they are not always in active shed. Sometimes adult worms are passed when deceased, in the pet’s stool.

Pets that are considered at risk (have fleas on themselves or in their environment, active hunters/scavengers, or pets that eat raw/undercooked meats) are recommended to be placed on a routine deworming protocol to prevent tapeworms from becoming a burden. Talk to Dr. Paterson next time you’re in, about setting up a protocol for your pet!

Deworming Puppies: What To Expect

Common Parasites That Affect Puppies

There are five main groups of parasites that commonly infect puppies:

Ascarids (roundworms)

Nematodes (hookworms, heartworms, whipworms)

Cestodes (tapeworms)

Coccidia (Isospora, Cryptosporidium)

Protozoa (Toxoplasma and Giardia)

Only a few of these parasites can be easily seen: tapeworms, whipworms and roundworms. The rest are microscopic, and they are identified in body fluids, primarily in the feces. So, if your puppy has diarrhea but you don’t see any “worms” that doesn’t mean parasites are not the cause! The most important being roundworms, hookworms, coccidia and tapeworms.

Deworming your dog: The seven most common mistakes – Labyes

Those of us who keep a dog as a pet generally know just how important it is to keep them parasite-free. But internal deworming is not always done correctly! Here we will help you identify the seven most common mistakes when trying to deworm your dog and how to prevent them.

Echinococcus multilocularis: Ontario, Canada

Echinococcus multilocularis, a small tapeworm with a big name, is causing big concerns in Ontario, an area that was until recently considered free of this parasite. This tapeworm is normally found in the intestinal tract of wild canids (e.g. coyotes, foxes) and can also infect dogs. That itself isn’t a problem, since the intestinal form of the worm doesn’t make these animals sick. The concern arises when something (or someone) ingests tapeworm eggs from the feces of an animal with the intestinal infection, potentially leading to a different form of infection called alveolar echinococcosis (AE). In this form, the parasite causes tumour-like cysts to form in various parts of the body, particularly in the liver, and the condition can be very difficult to treat by the time it is diagnosed.

In the normal life cycle of this tapeworm, wild canids shed eggs in their feces and those eggs are eaten by small rodents, who develop the parasitic cysts in their bodies. When a canid eats one of those infected rodents, the life cycle continues, as the parasite grows into its adult stage in the canid’s gut and produces more eggs.

That’s bad for rodents, but the problem is that this “intermediate host” stage can occur in more than rodents – it can also occur in dogs and people (and occasionally other species).

In humans, AE is characterized by a lengthy clinical incubation period of 5–15 years, during which the larval stage typically proliferates within the liver, behaving similarly to infiltrative hepatic neoplasia. Humans with clinical AE cases typically experience cholestatic jaundice, abdominal pain, fatigue, and weight loss. The preferred treatment is complete excision of parasitic tissue and radical resection of host tissue, depending on the site and size of the lesion, presence of metastases, and patient comorbidities. Benzimidazole chemotherapy is initiated at the time of diagnosis. In cases of total surgical resection, treatment is continued for a minimum of 2 years to reduce the likelihood of relapse. In case-patients who are not surgical candidates, chemotherapy treatment might be prescribed indefinitely to slow the progression of the disease. Historically, in patients from Alaska, France, and Germany, the average survival rate 10 years after diagnosis was 29% when left untreated. The advent of benzimidazole chemotherapy has increased the 10-year survival rate to ≈80%.

Alveolar echinococcosis has been diagnosed in a small number of Ontario dogs (with no travel history) since 2012, raising questions about how they got infected. The concern was that this parasite might have become established in our wild canid population, which would result in an ongoing and widespread risk to people and other animals and would be hard to control.

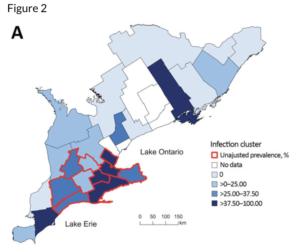

Those concerns have been proven true, by a study just published in Emerging Infectious Diseases (Kotwa et al. 2019). For this study, fecal samples were collected from 460 wild canids in Ontario. An astounding 23% of them were positive for Echinococcus multilocularis, with infection concentrated most heavily in the western-central part of the province.

What can we do?

Avoid contact with wild canids and wild canid feces as much as possible.

Do our best to prevent and treat intestinal infection in dogs.

Talk to Dr. Paterson about adding a preventative deworming protocol to your dogs health routine, if you would like to protect them against Echinococcus multilocularis.