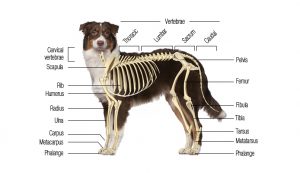

This week we’re looking at canine structure! We want the best for our beloved companions, and making sure they have a good ‘foundation’ is one of the best ways to start. You may have heard your reputable breeder talking about form, and function, but what does that all mean? Let’s have a closer look to better understand how our canine friends get around.

Structure and Movement PT 1

In humans and canines, body structure can be related to overall health. If a human has legs that are bowed out or bowed inward or if the spine is curved, that person is likely to suffer from pain and other health problems. The same can be true for canines and their structure even though there are structural differences between the species. Regardless of one’s breed, correct structure can be related to correct movement and good health.

In humans and canines, body structure can be related to overall health. If a human has legs that are bowed out or bowed inward or if the spine is curved, that person is likely to suffer from pain and other health problems. The same can be true for canines and their structure even though there are structural differences between the species. Regardless of one’s breed, correct structure can be related to correct movement and good health.

Read more HERE.

Part 2 HERE

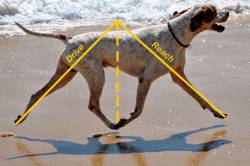

Dog Gait or Movement Terminology

Some of the common terms you will hear, in reference to your dogs gait. Complete with images, this will give you a better understanding of what each term means.

To Harness Or Not To Harness? That Is The Question…

You’ve probably noticed an upsurge during the last several years in the use of harnesses as an alternative to collars. At the same time, there has been a concern that harnesses might affect dogs’ gait. Researchers in the UK investigated exactly that question by comparing the effect of restrictive and non-restrictive harnesses on shoulder extension in dogs when walking and trotting (1).

TYPES OF HARNESSES FOR DOGS

There are two main categories of harnesses: those that are considered non-restrictive to front limb movement, which have a Y-shaped chest strap (Fig. 1), and those considered restrictive, which have a strap that lies across the chest horizontally (Fig. 2).

In this study, 9 dogs were moved at a walk and a trot on a treadmill wearing either no harness, a non-restrictive harness (an X-back mushing harness; Trixie Fusion harness), or a restrictive harness (Easy Walk harness). The researchers placed markers on the sides of the dogs’ legs and used video cameras to measure the angle of the shoulder when the front limb was in maximal extension (when the leg was placed furthest forward).

Some of their results were unexpected!

Read more HERE!

Do the Dew(claws)?

Do the Dew(claws)? © 2013 Chris Zink DVM, PhD, DACVP, DACVSMR, CCRT, CVSMT, CVA

I work exclusively with canine athletes, developing rehabilitation programs for injured dogs or dogs that required surgery as a result of performance-related injuries. I have seen many dogs now, especially field trial/hunt test and agility dogs, that have had chronic carpal arthritis, frequently so severe that they have to be retired or at least carefully managed for the rest of their careers. Of the over 30 dogs I have seen with carpal arthritis, only one has had dewclaws. If you look at an anatomy book you will see that there are 2 major, functioning tendons attached to the dewclaw. Of course, at the other end of a tendon is a muscle, and that means that if you cut off the dew claws, there are 2 major muscle bundles that will become atrophied from disuse. Those muscles indicate that the dewclaws have a function. That function is to prevent torque on the leg. Each time the foot lands on the ground, particularly when the dog is cantering or galloping, the dewclaw is in touch with the ground. If the dog then needs to turn, the dewclaw digs into the ground to support the lower leg and prevent torque. If the dog doesn’t have a dewclaw, the leg twists. A lifetime of that and the result can be carpal arthritis, or perhaps injuries to other joints, such as the elbow, shoulder and toes. Remember: the dog is doing the activity regardless, and the pressures on the leg have to go somewhere.

Perhaps you are thinking, “None of my dogs have ever had carpal pain or arthritis.” Well, we need to remember that dogs, by their very nature, do not tell us about mild to moderate pain. If a dog was to be asked by an emergency room nurse to give the level of his pain on a scale from 0 o 10, with 10 being the worst, their scale would be 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. Most of our dogs, especially if they deal with pain that is of gradual onset, just deal with it and don’t complain unless it is excruciating. But when I palpate the carpal joints of older dogs without dewclaws, I frequently can elicit pain with relatively minimal manipulation. As to the possibility of injuries to dew claws. Most veterinarians will say that such injuries actually are not very common at all. And if they do occur, then they are dealt with like any other injury. In my opinion, it is far better to deal with an injury than to cut the dew claws off of all dogs “just in case.”

Loss of Balance (Unbalanced Gait) in Dogs

Ataxia is a condition relating to a sensory dysfunction that produces loss of coordination of the limbs, head, and/or trunk. There are three clinical types of ataxia: sensory (proprioceptive), vestibular, and cerebellar. All three types produce changes in limb coordination, but vestibular and cerebellar ataxia also produce changes in head and neck movement.

Ataxia is a condition relating to a sensory dysfunction that produces loss of coordination of the limbs, head, and/or trunk. There are three clinical types of ataxia: sensory (proprioceptive), vestibular, and cerebellar. All three types produce changes in limb coordination, but vestibular and cerebellar ataxia also produce changes in head and neck movement.

Sensory (proprioceptive) ataxia occurs when the spinal cord is slowly compressed. A typical outward symptom of sensory ataxia is misplacing the feet, accompanied by a progressive weakness as the disease advances. Sensory ataxia can occur with spinal cord, brain stem (the lower part of the brain near the neck), and cerebral locations of lesions.

The vestibulocochlear nerve carries information concerning balance from the inner ear to the brain. Damage to the vestibulocochlear nerve can cause changes in head and neck position, as the affected animal may feel a false sense of movement, or may be having problems with hearing. Outward symptoms include leaning, tipping, falling, or even rolling over. Central vestibular signs usually have changing types of eye movements, sensory deficits, weakness in the legs (all or one sided), multiple cranial nerve signs, and drowsiness, stupor, or coma. Peripheral vestibular signs do not include changes in mental status, vertical eye movements, sensory deficits, or weakness in the legs.

Cerebellar ataxia is reflected in uncoordinated motor activity of the limbs, head and neck, taking large steps, stepping oddly, head tremors, body tremors and swaying of the torso. There is an inadequacy in the performance of motor activity and in strength preservation.

Read more HERE.

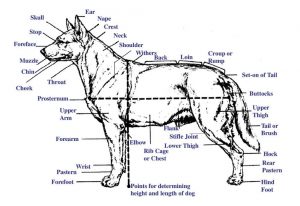

Canine Terminology – Say It Right

Every profession has its own specialized language. Call it jargon, if you will! The dog game is no exception. Old-time breeders of livestock, particularly horses, developed a language that served their needs for clarity and precision in defining the faults and virtues of their stock. The same terms with only minor changes carry over to the description of canine anatomy.

. Even the so-called experts are prone to overlook the esoterica in the use of anatomical terms. Take the word “hock”, for example. The hock is a joint on the hind limb located between the lower thigh and the rear pastern. Some breed standards, however, incorrectly use the term to mean the rear pastern, thus such phrases as “short in hock” or “long in hock”, which are technically incorrect. To say that the hocks are “well let down” or “set low” is correct and implies short rear pasterns.

Learn more HERE.